In memoriam: Alan Brotherton (1963–2015)

In memoriam: Alan Brotherton (1963–2015)

HIV Australia | Vol. 13 No. 2 | April 2015

Michael Hurley

Michael Hurley farewells an old friend and stalwart of the global HIV response, paying tribute to his work and life philosophies.

Elastic sided Blundstone boots,

Khaki shorts, a red truck and tales

Of derring-do on the foreshores of Botany.

Those were days of miracle and wonder.

This is a long distance call.

Alan Brotherton died of complications from melanoma on June 12, aged 51. He is survived by his partner Luke, by his parents, Alan and Doris, his brother Stephen, his sister-in-law Pauline, and his nieces, Isla and Kirsten. Friends and colleagues nationally and internationally have mourned his death.

Alan Brotherton died of complications from melanoma on June 12, aged 51. He is survived by his partner Luke, by his parents, Alan and Doris, his brother Stephen, his sister-in-law Pauline, and his nieces, Isla and Kirsten. Friends and colleagues nationally and internationally have mourned his death.

Alan’s family emigrated to Australia from the UK. He completed his secondary schooling in Canberra.

Few people know Alan began his working life as a trainee chemical engineer in the Wollongong steelworks.

I certainly didn’t know that when I first met him. Most of us came to know him as a stalwart of the Australian and international responses to HIV and AIDS.

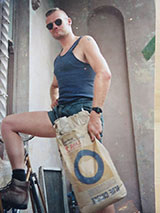

When I visualise him he is either in those shorts and a blue singlet or a blue suit and business shirt.

When I visualise him he is either in those shorts and a blue singlet or a blue suit and business shirt.

Alan played a major role in organising the international AIDS conference in Vienna in 2010 as Director, Policy and Communication for the International AIDS Society (IAS), and its conference partners and co-sponsors.

These partners included several UN agencies, the International Community of Women Living with HIV and the Global Network of People Living with HIV.

Prior to that he worked for two years in the UK with the International HIV/AIDS Alliance travelling extensively to partner organisations in affected countries.

Susie McLean, a Senior Advisor at the Alliance and formerly of AFAO wrote that Alan, ‘had an exquisite capacity to think deeply and differently, and to approach problems and dilemmas in HIV policy or programming with originality, drawing on the personal and avoiding generalisations and simplistic categories.’

In Australia, Alan was an activist in the early years of PLWHA (NSW), ACT UP and NAPWA. His activism was always linked to organised advocacy.

He worked for ACON initially in beats outreach, was President of NAPWA in 1996–1997, and then became the Education Manager at the Victorian AIDS Council/Gay Men’s Health Centre.

He returned to Sydney working briefly in policy at AFAO before becoming the first manager of the AFAO-NAPWA Education Team (ANET). He then managed education at the AIDS Council of South Australia.

Alan with Elaine (ACON volunteer) and Nic Parkhill (ACON CEO).

In the early 2000s he returned to ACON as Client Services Director, and then went to work at NSW Health in policy before heading off to the Alliance in the UK as a Senior Advisor – first in Policy then in HIV Prevention. From there he went to IAS, working with Robin Gorna, a former executive director of AFAO.

On his return to Australia he worked for ACON, this time in the role of Director, Policy, Strategy and Research.

On the day of Alan’s death, Nicolas Parkhill, CEO of ACON wrote:

‘Alan’s commitment to promoting the health needs of women in our community, both internally and externally, cannot be understated [nor can] his work to ensure LGBTI people have a rightful place in ageing, mental health, drug and alcohol and healthcare.

‘Alan could engage an audience like no other – always erudite and persuasive – and always delivered with … wit.’

I was first introduced to Alan when he was President of NAPWA. I met him, I think, through Scott Berry. Scott and Alan worked together on the national Positive Information and Education project.

The work of ANET followed the earlier Gay Education Strategies (GES) teamwork of Ross Duffin, Paul Martin and Keith Gilbert.

I had been an invited external advisor with GES and I worked closely with Alan in this time, first in ANET then as a Researcher in Residence. Somewhere in there he completed Honours and a Master’s degree.

One of the things Alan and I had in common was the belief that if you are going to be an out gay man you might at least take the trouble to make something of it. Alan did.

As Kirsty Machon said in a recent conversation, ‘Alan had a talent for living’. He liked good food and company and had eclectic tastes in music. He read widely, listened and thought. He partied.

Alan and his partner Luke.

He was kind, generous, principled and compassionate. He was also mentally tough. Those sparkling blue eyes could pierce and sliver. Mostly they did so good-humouredly.

Ben Tunstall, a friend of Alan’s in the UK, wrote poetically: ‘Each stab of his blunt sonnet shoots out from beneath a curling lip and one eye narrows to see it land, usually exactly where he planned.’

Alan gave me two fridge magnets and at least one snow dome. The first magnet is of Dorothy’s red shoes from The Wizard of Oz. He had remembered that when I was in Washington Dorothy’s shoes were on tour and I had missed seeing them.

The snow dome was from Patagonia. He knew I collected them and I recalled that as a much younger man he had gone to pick coffee as an international volunteer in Nicaragua.

He believed in the struggle for justice occurring there and elsewhere in Latin America. He was well travelled and totally committed.

The second magnet is wicked, ‘I used to care but now I take a pill for that.’ Someone who didn’t know Alan or hadn’t lived and worked through the worst of the AIDS epidemic might read that magnet literally. It is anything but.

In the defiant spirit of the early 1990s it is a multilayered, dark joke mixed with pain, mischief, insight, and irony. It is riddled with resilience.

He cared, but like many HIV activists Alan took empathy into another dimension, usually privately, because otherwise he was a public model of managed rectitude.

Alan made his own history out of personal and collective circumstance. Kirsty recounts a conversation in which he described coming to terms with his HIV status. He said he was standing against a wall in Spain eating a beautiful ripe peach and basking in the sun.

He realised there and then that he could live in the moment with all its pleasures. He said he didn’t remember a peach ever tasting as good, before then or after. Epiphanies however have a habit of reverberating long after a peach is finished.

As Bill O’Loughlin said at the funeral, ‘He was, quite simply, an unforgettable marvellous presence.’

Michael Hurley is a friend and former colleague of Alan’s.