Shaping the response for our communities.

Striving for virtual HIV elimination.

Health Equity Matters is the national federation for Australia’s leading HIV and LGBTIQA+ organisations. We are recognised both globally and nationally for the leadership, policy expertise, health promotion, coordination and support we provide.

Our impact areas

Uncovering the healthcare experience of our diverse communities.

Read the report where the diversity of our LGBTIQA+ communities were consulted on their experience of the healthcare system.

We hear common themes of an unsafe and damaging experience. This is compounded for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, multicultural communities, those living in regional and remote areas and people with disability.

We also find high rates of people from all our communities wanting access to LGBTIQA+ community-run health services.

Discover this and the other steps we need to take to ensure an accessible, affordable and affirming healthcare system for all.

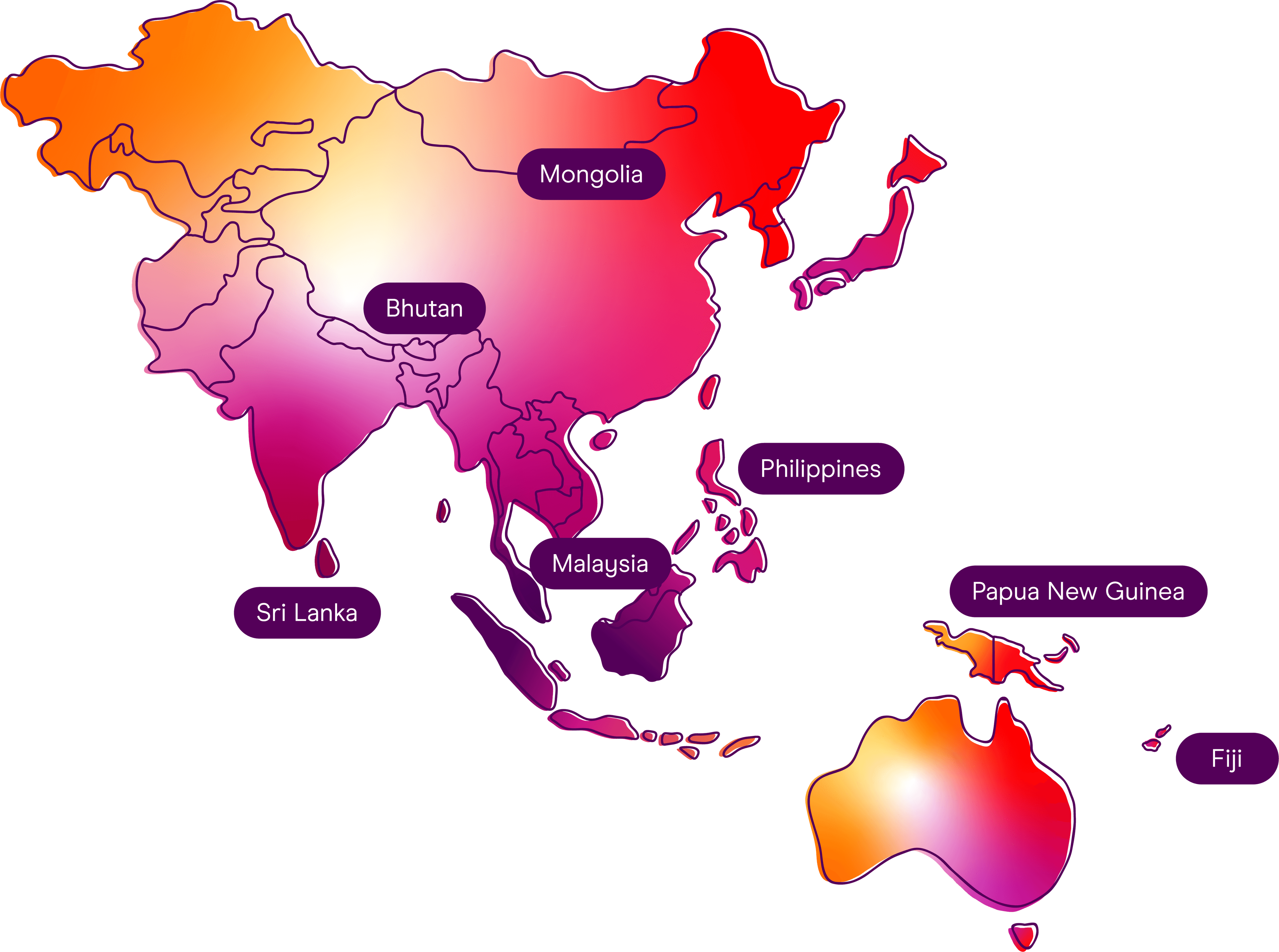

Our international impact

Since the early 1990s, Health Equity Matters’ International Program has worked to support stronger civil society responses to HIV, health and human rights in Asia and the Pacific.

More recently, our international team leads multi-country programs in Asia and the Pacific to ensure responses to HIV are sustainable.

Our activities and achievements

Health Equity Matters’ 2023-24 Annual Report provides a snapshot of our activities and highlights the year’s achievements, both in Australia and overseas.